There are different textbook definitions provided about the concept of collective bargaining, and references have been drawn to some of them in the body of this chapter. For simplicity and clarity of understanding, the author has provided a first-hand or stand-alone definition of the concept as outlined below:

The above definition demonstrates a compendium of functioning activities that enable the existence of smooth operation to exist in the workplace environment – the relevance of this topical discourse, which is related to the SDG agenda item of “Decent Work and Economic Growth” will be very well received as the intensity of the impact of Corona Virus 2019 (notably referred to as “COVID-19”) unveil itself once life begin to normalize.

The collective bargaining agreements terminology as used nowadays was first coined in 1891 by Beatrice Webb – this is connected with the field of industrial relations, which commenced in Britain (Wilkinson et al. 2015). This has been done to enhance welfare conditions for workers, who during the rise of trade union activities in the eighteenth century needed some level of protection to support issues pertaining to illegal dismissal, severance packages, decent pay level that takes account of changed economic conditions like demand and supply-side shocks, which normally result in inflationary pressures. With the rise of industrial revolution in the United States, the enactment of the “National Labor Relations Act” of 1935 then made it quite illegal for employers to deny union rights to an employee (Pope 2006; Atleson 1983). This was seen as wise move to protect vulnerable employees from being dismissed without much protection to defend their rights while in employment.

Moving on at the international level, the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” which was sanctions by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948 (Nurser 2005; Feldman 1999), then paved the way for a form of universal protection for humanity, particularly in terms of voicing out concerns while in paid employment. The announcement of such a universal declaration was seen as a way of recognizing the inherent dignity and rights of everyone across the world, and is also considered the engine of peace, freedom, justice, and tranquility when dealing with negotiations on employee-employer matter. These, to a greater extent, have been widely expressed in the United Nations Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions goal (related to SDG agenda item number 16), which is hoped by 2030 will be received universally so as to bring sustained peace and easy means of co-existence in the universe.

There is a need to avoid the situation of “bargaining impasse,” which seem to be quite common prior to the announcement of the Universal declaration of human rights; such uneasy action normally results in total loss to both employees involved and the organization as well – the unrecognized state of trade union groups was mostly seen as the root cause of bargaining impasse in dealing with employees’ concerns within an organizational setting. As emphasized in the preamble of the declaration of Human rights charter, it is very essential that institutions of all types (be it public or private sector) must seek to avoid employees’ recourse to strike actions as a last resort. Such decision involving strike actions normally have devastating consequences to both employers (whose productivity can almost be seen in a state of wreckage, particularly with the prolongment of trade union strike actions) and also to employees, which include loss of earnings, and ultimately deprivation of access to livelihoods for families and communities at large.

The concept of collective bargaining agreements is widely encompassing, but as emphasized in Newland’s (1968) study, the central issue seems to gravitate within two theoretically led categories, namely, “economic matter and rights and obligations of the parties.” In a world where the main reason for a person’s passion to engage in employment is to address livelihood needs – either in pursuit of the self or addressing family needs – it means that the economic matter would seem to take priority in negotiating better deal to address economic well-being and prosperity. In many situations, both union representatives and employers would normally present a case that maximizes their share of limited, but fixed resources. In this vein, the fact that resources are perceived to be limited meant that each party would be very highly prepared to exercise their power to maximize greater share of the negotiation process.

On a more theoretical standpoint, collective bargaining agreements can be linked into three levels of classification: “mandatory, permissive and illegal” – the concept which Saylordotorg (Online) also defined as “the process of negotiations between the company and representatives of the union.” In the case of mandatory bargaining, one would consider it to fall within topical concerns like wages, health and safety at work, management rights, work conditions, and benefits. On most occasions, permissive discussions are not something that seen to be categorized, but can be discussed, and these may include concerns around drugs testing or resources like access to cellular phones that would normally require employees to perform specific task(s), but for which there are no legally enforcing requirements. Illegal topics are normally viewed as discriminatory to employee-employer collective bargaining negotiating processes, and hence are treated cautiously, except where trivial issues are said to dominate the dynamics of collaborative bargaining discourses.

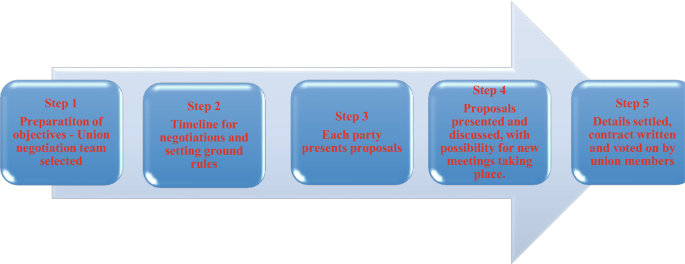

In view of the aforementioned discussion about collective bargaining agreements, the entire process of engagement would typically involve five steps as outlined below.

Figure 1 presents a case of the five different stages of collective bargaining processes as would be expected during negotiation between employer and employees, normally represented through selection of trusted union members, who would be expected to speak on behalf of staff issues or concerns. The first stage basically involves preparation of union representatives – they are usually expected to present staff concerns to an employer. It is therefore essential that union members selected are very well au fait with the organizational structure, particularly staff concerns presented to an employer. Despite not expected to be fully trained in negotiation, those represented should be able to demonstrate such quality, given the trust placed upon them to speak on behalf of staff concerns, which in most cases will gravitate around welfare and pay conditions in view of price dynamics or inflation trend. Equally, the employer would normally be prepared to receive staff concerns/demands and, ultimately, prepare for amicable compromises on items presented by union representatives.

Step two addresses timeline for which negotiation is expected to conclude – there is an expectation of ground rules to be set upon, which means that points raised by union members can be negotiated in a manner that is expected to address staff concerns. Despite union members are not expected to make decision(s) about the employer’s offer, there is an anticipation for them to present a firm case that is capable of addressing employees’ concerns in a bid to avoid delay and the possibility of a call to bargaining impasse. Lack of amicable negotiation can give rise to series of economic strike action, which is more common in institutions given the situation of staff disgruntlement about deplorable welfare conditions during their employment in an organization. There are ramifications, which can result from economic strike as staff, with support from national union consultation, will be inclined to organize series of sit-down strike actions. Instead of attending to work duties, union representatives can request a situation where staff members are instructed through majority vote to take no action on operational activities until proper negotiation is actioned between the employer and union representatives.

In step three, detailed proposals are presented on the table for discussion by both parties. This normally involves an opening statement, with a view that both parties will be prepared to display rationality in a bid to allowing things to work in the best interest of an organizational goal. This is not a point where parties are expected to accept offers made, but an opportunity to scrutinize offers, with a view of scheduling further meeting(s), which in this case will give rise to Step four.

In Step four, proper consultation will be expected to convene in the best interest of both parties, bearing in mind that an employer will only present a confirmed offer with consideration given to resource limitation. It is therefore expected details of such situation should be tabled for discussion, which will enable union representatives develop rational understanding about the reality of what the employer is really capable of offering, given prevailing circumstances of resource constraints, particularly for competitively private sector organizations.

In the event an agreement is arrived at by all parties concerned as mentioned in stage four, there is the possibility that a new contract can be drawn, setting out details of issues discussed and settlements agreed upon by both the employer and union representatives. At stage five, written contracts are then drawn. At this point, it is incumbent on union representatives to explain details of an employer’s offer to staff – this can be done through an open meeting or at departmental level so as to allay staff worries about their concerns and well-being. With reference to ILO (2015a), the concept of Collective Bargaining is construed as a process “incorporating all agreements in writing regarding working conditions and terms of employment concluded between an employer, a group of employers or one or more employers’ organisations, on the one hand, and one or more representative workers’ organisations, or, in the absence of such organisations, the representatives of the workers duly elected and athorised by them in accordance with national laws and regulations, on the other.” It is believed that a written collective bargaining agreement should take cognisance of the following:

There is a need for collective bargaining agreements to be made an integral part of society’s endeavors in a bid to enhance welfare conditions for the benefit of those in employment. Across the global community, living conditions seem to be taking a dynamic trajectory given cost-push pressure on production of goods and services, and more recent is the case with COVID-19. Invariably, there is a direct pass-through effect of such cost-push pressure from producers to consumers or economic agents, which normally comes in the form of high prices paid for the consumption of services and goods consumed. Equally and most importantly, with the rapid change in prices of goods and services purchased by consumers, it is almost impossible for people to afford the means to meet decent living, more so the sustainability of addressing basic welfare needs associated with housing and other essential items.

When one looks at the objective focus of institutions like central banks across the world, which are geared toward utilizing professional expertise to explore economic realities like forecast outcomes (using a range of macroeconomic variables) in assessing price dynamics, it is but certain for efforts to be explored by union representatives in setting up collaborative bargaining agreements that support decent and sustained living conditions for humanity (see Jackson et al 2018; Jackson 2018; Jackson and Tamuke 2018; Tamuke et al. 2018; Jackson et al. 2019). The essence of collective bargaining as rooted from the SDG 2030 agendas is to address concerns bothering around improved working conditions, in a bid to maximize the most favorable returns to both employers and employees.

The rationality for decent economic well-being needs to be given high priority in the under-developed economies, where very little seem to be done in protecting employees’ sustained welfare. Lag effects in addressing the reality of economic well-being in these economies is somehow understandable, if one is to take the driving seat of becoming an employer – considering the pressure of fluctuations in global outlook of core economic indicators. This in reality would reveal itself through series of supply-side shocks, which normally emanate from the global community, for example, exchange rate issues, seen as the key driver of frequent price fluctuations in weak economies, despite policy measures set in place to stabilize prices (See Jackson et al. 2020; Jackson and Jabbie 2020a; Bangura et al. 2012).

Decent welfare for people is an essential part of life and, most importantly, the need for people to develop motivation in support of organizational objectives. Sustainable living is an essential element of the UN SDGs; it is seen as the core of decent living and prospect for growth in the global economy. This situation is very hard to achieve in developing economies, particularly weak economies in the Sub-Saharan African (SSA) region, because of their susceptibility to shocks – such situations can be blamed on the overreliance on import of essential and basic commodities to sustain lives, instead of efforts being devoted to improve the productive sector, otherwise referred to as the “real sector” in economics. Due to the prevalence of the aforementioned structural weaknesses, it is seen for many of these economies that, even with the use of considered policy measures actioned by policy-led institutions like central banks, it is still a hard thing to realize economic stability in the short run, which is considered an essential ingredient for decent livelihood sustainability as addressed in the SDG8 charter. In many of the SSA economies for example, it may be seen that policy measures are more or less undermined given myriad of structural problems faced by many of the region’s weak economies – for example, unproductive and weak real sector as seen more lately in post war-torn countries like Sierra Leone and Liberia (Jackson 2019; Jackson and Jabbie 2020a).

On reflection of the concept of collective bargaining agreements as linked with the United Nations 17 proposed Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs], efforts should be stepped up to address inequality of welfare conditions faced by people in the global community. Given the experience of open democracy as practiced in developed economies like the UK and the USA, the voices of pressure groups in championing collective bargaining agreements seem to be working, particularly with the emergence of diversified range of pressure groups like feminist actions, who have also witnessed a new wave of critical concept around issue like intersectionality (see Jackson and Jabbie 2020b; Jackson and Jackson 2020), senior citizens, and many more. On the contrary, such economies seem not to have gotten firm grip of the essence of collective bargaining agreement; this is partly due to low level of education that is lacking among citizens, and in many cases, selfishness on the part of those in authority to judiciously invest in human development, considered an essential tool for sustainable growth and development (Jackson et al. 2020; Jackson 2015, 2018a, b).

On dissection of the 17 agendas for SDGs, which are expected to be in full operation by the year 2030, it seems very clear that at least seven of these are directly associated with the concept of collective bargaining agreement as elucidated below:

The above are thought of as essential tools in driving the way forward in addressing human sustained welfare, given the failure of those in governance to disregard concerns raised by union representative, particularly in the workplace environment to negotiate decent living conditions.

In a bid to promoting good relationship in collective bargaining agreements, it is but necessary that governments across the globe make it a mandatory call through the national labor ministry to protect employee-employer relationships. Employees are normally placed in a vulnerable state, particularly in developing economies where employers in the informal sector are seen to be taking advantage of workers’ vulnerability due to the deprived state of these economies (Jackson 2020). In this regard, employment laws should be directly linked in ensuring industrial relations is made an integral part of the workforce, and most importantly a situation where employees’ rights are treated seriously. This should take account of wider areas of concerns pertaining to wage/salary, linked to inflationary pressures, which means that workers will be better placed in the event of an economy not performing well, where prices of goods and services moving at an escalated rate, to the disadvantage of welfare loss to those in low income level employment. As addressed in the SDG1 and 3 agendas, governments in the global economy and more so developing countries around the SSA region should be made aware about the essence of life, which is to ensure that purpose of people engaging in work is to alleviate living conditions, and ultimately, reducing the chances of being in poverty.

In this regard, there should be an effort made by governments and international partners like the International Labour Organisation and the United Nations to emphasize the interconnectedness of the various SDGs that embodies improvement in welfare conditions for people in the 2030 charter. In this regard, reference should always be linked to the “Manual on Collective Bargaining and Dispute Resolution,” more so for those working in the Public Services (ILO 2015b) so as to reinforce evidence of good practices in preventing disputes between employees and employers generally in the workplace environment. Such approach is also in line with the Articles 7 and 8 of the ILO Convention, which is done as a way of addressing dispute issues and resolution on labor relations in the Public Services – such articles can also be made universally accepted even for those in the private sector that feel very unprotected when it comes to dealing with fair treatment on issues pertaining to collective bargaining agreements (also part of the SDG8 charter on Decent Work and Economic Growth).

In a bid to promoting decent work, which also accounts for prospect for economic growth and prosperity in the global community, it has been made clear from the onset of this chapter that favorable collective bargaining agreement is essentially vital to promote sustainable living for those in employment. In this regard, there is a need for collective efforts to be made, whereby all the relevant SDG agendas should be made interconnected to address a situation of cohesiveness between those representing employees’ interests (in this case union representatives) and the employers or their legal representatives.

There is plethora of gains to be made when efforts are effectively championed to improve cooperation in the area of employment relations, more so for the good of economic prosperity in a nation. In this regard, economies are sure to benefit through high level of productivity when employee and employer relations are well coordinated in situations of dispute of issues dealing with employees’ dissatisfaction. The most important and highly publicized issues that seem to be promoted in the media about employee-employer bargaining agreements are to do with pay/wage condition. This is quite important, given the fact that the main reason for people taking up work is to address livelihood concerns, and the way such transaction can be demonstrated is through monetary exchange, which require transfer of money (physically or through electronic means as seen in modern time).

In the world of uncertainty, which is highly dictated by shocks that come in the form of unexpected events within an economy or in the global community as seen in the case with oil price changes, it is obvious that weak economies are left in a vulnerable state to sail through impacts of shocking events. Such impacts would normally be seen through supply-side shock, revealing itself through exchange rate dynamics. For weak economies (more so those in the SSA region) that are highly dependent on the importation of essential items to sustain lives, the pass-through effect will be clearly seen through high prices for basic commodities and services consumed. Given the experience of aftermath supply shocks in the 1970s, researchers have developed keen interests in the weaknesses of collective bargaining agreements, without much consideration given to macroeconomic adjustments, which can impact on livelihood sustainability (Flagan 1999; Christofides and Oswald 1992). In situations where employees are inclined to request for adjustment in pay/wage conditions on account of a drop in standard of living, it is vital that employers display maturity and understanding to the reality of things happening, while also coming clean about the reality of resource limitation at their disposal.

Equally, employers will also be faced with serious level of constraints, particularly in the public sector, where expenditures for service delivery would have been determined, without much consideration given to unexpected shock outcome. In the event of such a situation occurring, it is very important that collaborative efforts (between employers and employees) are devoted to ensuring that each side of the negotiating table manifests understanding about the reality on ground; in this case, ensuring there is calmness in working practices, despite the impact on livelihoods, seem to manifest itself through high price adjustments of goods and services. Employers would need to demonstrate skillfulness in their approach to dealing with such trivial matters, while also expressing their understanding of the reality, with regard to the adjusted high cost of living.

In a bid to moving forward, the worse situation of bargaining impasse should be avoided during collective bargaining agreements. No matter how difficult a situation is, both employees and employers should at all time seek to demonstrate high level of restrain in minimizing problems that will result in economic strike actions being voted upon by employees. There is plethora of ramifications to be faced when a strike action is used as the ultimate means of addressing problems and to name a few, “loss of earnings to businesses, particularly in the case of profit making institutions, loss of livelihoods to individuals or households, economic loss to productivity for both the state and businesses, and where such action is to recourse to violence, this may result in economic loss to a state, etc.”

In conclusion, and as a way of moving forward with collective bargaining agreements, it is necessary that the following points are considered seriously:

On a final note, progress in developing sustained collective bargaining agreements will require collaboration and the ability to be inclusive in decision making. In this case, both employees and employers must ensure systems are continuously reviewed, with the scope of ensuring both parties are at the benefit of contributing to society’s long-term scope for development and growth through cooperation.

Views expressed in this chapter are those of the author and do not reflect any of the named institutions for which he is associated.